This is a piece by our new economic contributor,

. I’d also like to give a shoutout to John Stepek (Senior Editor at Bloomberg UK) whose article, alongside the Economist’s article are sources of inspiration for my post.The parallels between medieval England's disastrous wage controls and today's minimum wage policies reveal uncomfortable truths about government intervention in labour markets. While separated by seven centuries, both represent attempts to manipulate wages that have produced strikingly similar unintended consequences - worker demotivation, economic distortions, and social upheaval that challenges traditional class structures.

Lessons from the Black Death Era

Following the Black Death's devastation of England's population in the 14th century, King Edward III faced a labor shortage crisis that drove wages skyward. His solution - implementing comprehensive wage and price controls in 1349 - offers a cautionary tale that resonates powerfully in today's policy debates.

The medieval wage caps, enforced through a brutal system of public stocks and informants, created a workforce of deliberately underperforming laborers. As historian Anton Howes documents, employers complained constantly about workers who "were plain lazy, getting drunk and slacking off at work." This was rational economic behavior, despite what some may think. When monetary rewards were artificially capped, workers simply refused to expend commensurate effort.

Employers, unable to compete through wages, were forced to offer increasingly elaborate non-monetary benefits: better clothing, superior food and drink, and more pleasant accommodations for live-in staff. Parliament's 1363 attempt to ban these workarounds had to be repealed within a year, demonstrating the futility of comprehensive wage controls.

The economic damage extended far beyond individual workplace dynamics. These policies, which Howes argues lasted longer and proved more economically damaging than previously understood, created a "dystopian nightmare" for workers while hampering England's economic development relative to continental Europe for centuries.

Britain's Contemporary Wage Revolution

Fast-forward to modern Britain, where a different form of wage intervention has produced remarkably similar distortions. The country now faces what can only be described as a social and economic revolution disguised as routine policy adjustment.

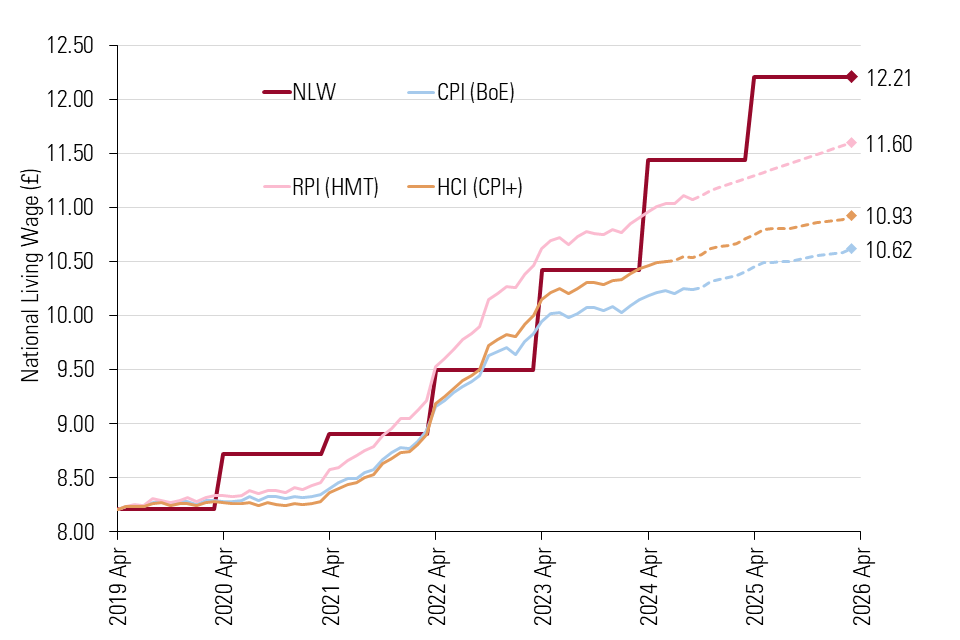

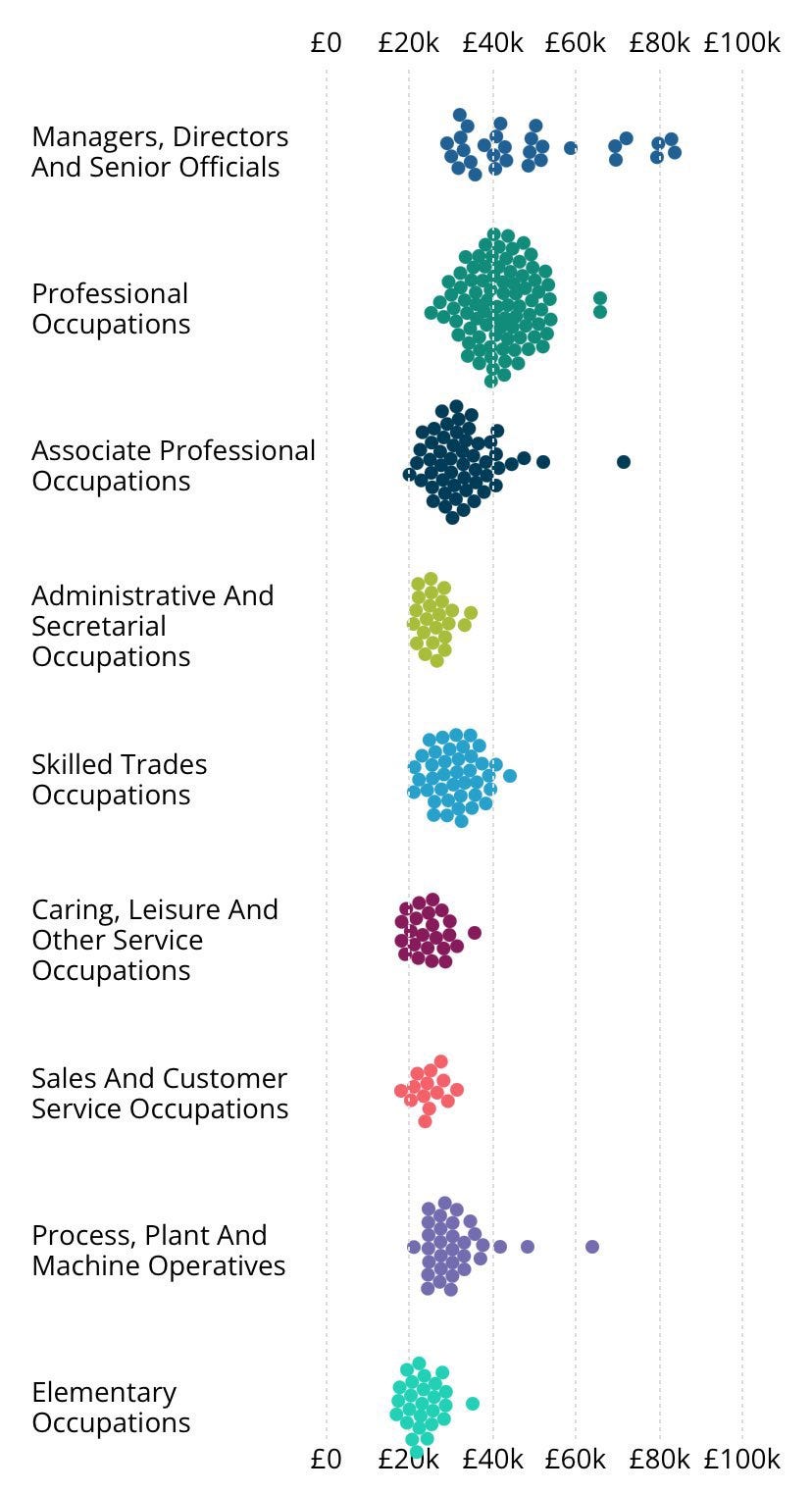

Consider the stark reality facing today's graduates: a marine conservation position requiring "at least a high upper-second degree and excellent A-level results" pays £25,300 annually, virtually identical to what a full-time minimum wage worker will earn at £12.21 per hour. This isn't an isolated anomaly but representative of a fundamental reshaping of Britain's economic hierarchy.

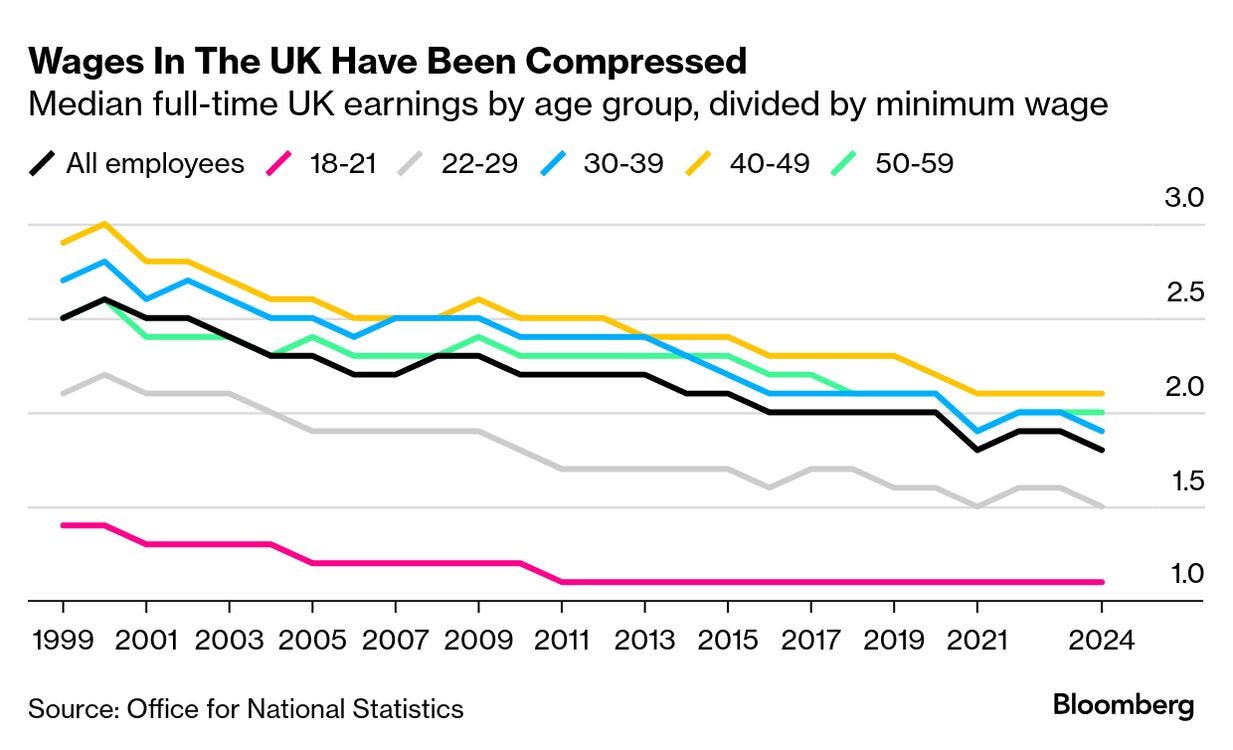

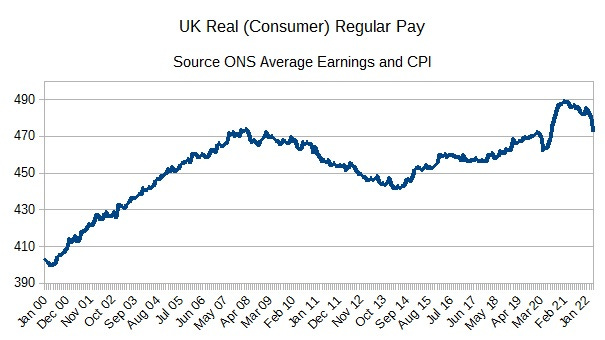

The data reveals the extent of this transformation. In 1997, a median earner in Britain took home almost double the income of someone at the tenth percentile. By 2023, that gap had shrunk to just 50% more; a compression driven almost entirely by aggressive minimum wage increases that have pushed the statutory minimum to two-thirds of median income, among the highest ratios globally.

This compression has created winners and losers in ways that defy traditional economic expectations. Bar workers, cleaners, and shop-floor staff - traditionally precarious professions - have enjoyed what can only be termed a "relative bonanza." Median hourly wages for bar workers jumped 26% in real terms between 2011 and 2023, while median salaries overall managed a paltry 1.9% increase.

The psychological and social implications are profound. Many employers and job seekers haven't fully grasped how dramatically the landscape has shifted. Job advertisements still appear seeking junior graphic designers with degrees and two years' experience for £22,000 - soon to be below minimum wage - or climate organizers fluent in English and French for similar amounts.

The Professional Class Rebellion

The compression's most visible manifestation has been the revolt of educated professionals who suddenly find their credentials and training financially devalued. Junior doctors represent the most organized and vocal example of this phenomenon. Their union, the British Medical Association, made strategic use of wage comparison, highlighting that Pret A Manger employees could earn more than medical professionals; a messaging strategy that ultimately secured them a 22% pay raise over two years from the incoming Labour government.

This professional uprising reflects deeper anxieties about social status and economic recognition. The question isn't merely economic but existential: in a country as class-conscious as Britain, what happens when middle-class professions attract working-class wages? Perhaps nowhere is this paradox more acute than in Britain's emerging tax trap for graduates. The convergence of the £25,000 student loan repayment threshold with minimum wage earnings creates a perverse situation where any graduate working full-time - whether stacking shelves at Tesco or training as a lawyer - faces a marginal tax rate of at least 37%.

This has created what amounts to a discriminatory tax system based on education rather than income. Graduates take home less money than non-graduates earning identical amounts, while pensioners remain exempt from national insurance contributions entirely. The result is a tax structure that penalizes education and creates distinct classes of citizenship based on academic credentials and age.

The Political Consequences of Economic Distortion

The political ramifications extend far beyond immediate economic impacts. Research by Ben Ansell and Jane Gingrich reveals that graduates working in non-graduate roles are significantly more likely to vote for radical-right parties than their peers in graduate-appropriate positions. The "never made it" cohort represents as much of a political threat as the traditional "left behind" working class.

This creates a potentially explosive alliance between disparate groups united by economic grievance. When a Radio 5 presenter attempted to extol minimum wage virtues, an angry lorry driver captured the sentiment perfectly: "What's the point in you working extremely hard if you can earn almost the same just doing minimum-wage jobs?" The alliance of lorry drivers and doctors would be curious but potentially powerful.

The Illusion of Costless Policy

For policymakers, minimum wage increases have represented the closest thing to a free lunch in public policy. The benefits [higher wages for the poorly paid] materialized immediately and visibly. The costs - unemployment, business closures, reduced hours - were expected but never seemed to arrive in significant numbers.

This apparent success created what economists might recognize as a classic policy addiction. Like laboratory monkeys with unlimited access to reward mechanisms, successive governments of both parties have raised minimum wages at virtually every opportunity, mistaking the absence of immediate visible costs for the absence of costs entirely.

Yet the medieval experience suggests these costs don't disappear; they transform and migrate. Instead of unemployment, modern Britain faces worker demotivation reminiscent of 14th-century England. Instead of business closures, employers increasingly compete through non-wage benefits and working conditions. Instead of reduced hours, there's a growing disconnect between effort and reward that undermines productivity and economic dynamism.

The Speed Limiter Effect

Modern minimum wage policy functions essentially as an economy-wide speed limiter. While not technically a maximum wage, aggressive minimum wage increases create practical caps on wage growth throughout the economy. The more rapidly minimum wages rise, particularly in businesses and industries employing large numbers of minimum-wage workers, the harder it becomes to maintain meaningful wage differentials between junior and senior roles.

This compression effect ripples upward through the entire wage structure. Deutsche Bank analysts note that wage compression has accelerated dramatically, with the gap between the bottom tenth of pay and median wages shrinking by five percentage points in just five years. For full-time workers, those in the lowest decile now earn 65% of median wages; for part-time workers, it's more than 85%.

When combined with other policy interventions—the graduate tax of 9% on earnings over £25,000, marginal tax rates of 62% (or 71% including the graduate tax) on earnings between £100,000 and £125,140—the entire system becomes antithetical to economic striving and advancement.

Historical Lessons and Modern Blind Spots

The medieval experience offers crucial insights that modern policymakers have largely ignored. Price controls, whether on rents, consumer goods, or wages, consistently produce more harm than good over time. The immediate benefits are visible and concentrated; the long-term costs are dispersed and often attributed to other causes.

Medieval England's wage controls lasted for centuries precisely because their negative effects were gradual and often manifested in ways that seemed unrelated to the original policy. Worker demotivation, reduced innovation, slower economic growth, and social tension all appeared to have independent causes rather than representing systematic responses to wage suppression.

The Competitiveness Question

Proponents argue that wage compression might make Britain more competitive by reducing inequality and potentially lowering overall labor costs. There's some theoretical appeal to this social democratic vision, a society where those in the middle accept lower wages knowing that those at the bottom are better off.

However, the medieval experience suggests this optimism may be misplaced. England's wage controls coincided with a period of relative economic decline compared to continental Europe. The systematic suppression of wage incentives appears to have undermined the very productivity improvements and innovations that drive long-term competitiveness.

Modern Britain risks repeating this historical pattern. When economic advancement requires exceptional effort, skill development, and innovation, but the reward structure has been flattened through government intervention, the rational response is to reduce effort to match compensation, exactly what medieval employers observed seven centuries ago.

Recognising the True Costs

The minimum wage has undoubtedly improved conditions for Britain's lowest-paid workers, representing a genuine policy success in narrow terms. But this success has come at costs that are only now becoming visible - the demotivation of middle-class professionals, the creation of perverse tax incentives that penalize education and advancement, and the emergence of political coalitions united by economic grievance rather than traditional party loyalties.

The medieval precedent suggests these costs will compound over time. What begins as worker demotivation evolves into broader economic stagnation. What starts as social tension between classes becomes political instability that undermines the entire system.

The challenge for contemporary policymakers is recognizing that successful policy interventions can become destructive when taken to extremes. The minimum wage worked well when it provided a reasonable floor for the lowest-paid workers. It becomes economically and socially dangerous when it begins to function as a ceiling for the aspirational middle class.

As Britain grapples with productivity challenges, political polarization, and questions about its economic future, the lessons of medieval wage controls offer both warning and opportunity. The question is whether modern politicians will prove more capable than King Edward III of recognizing when well-intentioned policies have exceeded their useful limits and begun to damage the very society they were designed to protect.

Thanks for reading! What are your thoughts? 👇

Check out this week’s other article: https://lbdispatch.substack.com/cp/173439139

Thanks for this AMAZING article, Les! People don't usually realise this about minimum wages!

This is my first article for State of the Debate, and something I've been wanting to write about for a while. Not enough people know about wage compression in the UK and the effects it has on workers across the income spectrum.